History of the Optimists

Optimist Clubs participate in community service programs that are dedicated to bringing out the best in kids. Since each Club is autonomous and run by members in their community, Optimists have the unique flexibility to serve the youth of their area in any way they see fit.

Optimist Clubs are dedicated to “Bringing Out the Best in Kids” and do their part through community service programs. Since each Club is autonomous and run by members in their community, Optimists have the unique flexibility to serve the youth of their area in any way they see fit. Optimist Clubs see a need in their community and react to it.

The First Optimist Club

The first recorded “optimist” club in the world was really a “non-pessimist” club. Sir Richard Steele, an Irish-born English playwright, wrote of his membership during the early 1700s in a club of ten to twelve businessmen who banished members if they showed sourness of disposition, spoke impatiently to servants or exhibited any trace of pessimism. The group was called the Good Humor Club.

The appearance of service clubs as we know them didn’t occur until the early part of the 20th century. After the widespread economic panic and depression of the early 1870s, there were marked advances in agriculture, industry and commerce. Keeping pace with these material improvements was a whole new pattern of thinking where social advances were concerned. As nations emerged from predominately agricultural societies, where individuals were primarily concerned with their own well-being, citizens began looking beyond their own self-interests. People began grouping together to combine their talents and energies to bring about change.

Those who believed they could change things for the better called themselves optimists. It’s unknown how many service clubs in North America before 1900 were called Optimist Clubs, although several are listed in rare old city directories and guides. In May of 1895, the Queen City Optimist Club was formed in Cincinnati, Ohio, by prominent civic leaders who wanted to work for the civic and cultural betterment of the city. Old records indicate this club was involved in city beautification programs, various welfare and charity projects, as well as pioneering attempts in the field of youth programs. But through the death of its old members and the lack of a continuous transfusion of new members, plus the gradual loss of club activity in civic projects, this Optimist Club declined and finally died. The last published mention of it was in 1902.

A newspaper item appearing in a Watsonville, California, paper dated July 12, 1904, announced that “The Optimists is the name adopted by an organization of young men – members of the Methodist Episcopal Church of this city.” The article mentions a constitution and bylaws being adopted and permanent organization being effected the day before. No trace of that club exists today. On November 11, 1905, the 129 members of the Optimists Club of Chicago held their first annual banquet. The program lists no fewer than 14 speakers, plus the campaign remarks of six men who announced themselves as “candidates for the directorate.” There is no historic chain of events that forms definite links between the first Optimist Clubs, organized just before and after 1900, and the first movement toward unification.

The Optimist label was being used by several clubs whose members – representative business and professional men in urban communities – had banded together for their mutual benefit. There may have been some correspondence between individual members of the widely scattered clubs, but none of these clubs remained in existence long enough to become links in a national chain. Early Attempts at Organization In early 1911, a young insurance man from Buffalo, New York, E.L. Monser, dropped by the office of his friend, Charles Grein. Monser described an idea he had picked up from his travels “in the West” to organize a club of men from different businesses and professions and promote the old “you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours” system. Grein liked the idea and agreed to host a meeting in his office. On February 16, Monser and Grein met with O.L. Neal, a dealer in Victrolas and Indian motorcycles; Eugene Tanke, a jeweler; and J. Raymond Schwantz, a brewer. And so was born the Optimist Club of Buffalo.

By April they had 25 more men interested in the club and elected their president, agreed upon the fundamental purposes and picked the time, place and regularity of their meetings. And while they started off enthusiastically, things were rough at first. “There followed months of disappointment and delays,” one of the founders wrote in 1915. He added, however, “Since we had adopted the name of ‘Optimist’ nothing could come but success.” By 1915 the Buffalo Optimists had conducted the first new club building efforts, with clubs formed in Syracuse and Rochester. These three clubs soon realized it was as difficult for clubs to operate independently as it was for men, and so they incorporated as The Optimist Clubs of New York State. This was the first attempt at any unification of Optimist Clubs.

The Birth of a Formal Organization

As a part of the celebration of the Indianapolis club’s first anniversary, representatives from all the other known clubs were invited to a conference in the Indiana city in May of 1917. On the 18th and 19th of that month delegates from 13 clubs—Indianapolis, Louisville, St. Louis, Milwaukee, Denver, Chicago, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., Peoria, Minneapolis, Springfield, Baltimore and St. Paul—gathered, without authority to act on behalf of their respective clubs, to discuss the possibility of formalizing a national organization.

Though not a convention in any sense of the word, the conference did generate a new feeling of unity and general awareness of the great potential in optimism. As one delegate wrote afterward, “Harmony was the keynote and every delegate seemed much impressed with the future of this new venture.” But it was not to be. The clouds of World War I were rolling over the United States and the hopes of organizing optimism were beginning to fade. Optimism Gets Dealt a Heavy Blow By the spring of 1917, the United States was mired in the First World War, and by autumn of 1918 all major industries had either converted to war work or were practically out of business. The cost of living had jumped 17 percent, sugar was being rationed and people were saying that what the war didn’t get the influenza epidemic would. By November, and the Armistice, shortages were reported in everything from beans to baseball (the season had been cut short by order of the Secretary of War). Few Americans were thinking optimistically and fewer still were interested in joining a club of optimists.

The older clubs were becoming dissatisfied with the American Optimists Clubs, largely because of a group of professional organizers who had assumed control of the organization. Some clubs began to talk of secession from the national group and of forming their own organization. The members of the Kansas City club felt that the Optimist movement was a thing of such value that a new nationwide organization should be established. As a result, a non-profit corporation was formed known as the American Optimist Club and letters were sent to all known clubs asking them to join in a first convention. Most clubs indicated their willingness to participate; however, the Indianapolis club suggested that the meeting be held there rather than in Kansas City since national headquarters had formerly been located there. All concurred in the merits of the suggestion and a conference of the disgruntled clubs was scheduled for March 1919 in Indianapolis. This may have been the most crucial meeting of club delegates in the history of Optimism. That anyone would be able to get representatives from any dissatisfied group to journey across the country via train to discuss their peeves was in itself a major phenomenon and an exhibition of the fundamental spirit of optimism that infused those individuals.

The 11 clubs represented at this meeting nullified the secession notions, settled their differences and chose a new name for the organization: the International Optimist Club. Incorporation papers were filed with the Indiana Secretary of State and a temporary slate of national officers was appointed. Delegates returned to their clubs with a revitalized spirit of Optimism. Above all, the seed that would later become Optimist International had been planted. A national convention, the first, was called for June 19 and 20 of that year, to be held in Louisville, Kentucky. Little did those dozen or so Optimists realize what their decision to meet again would lead to. Optimists gather at the first convention of Optimist International in June 1919.

The 1920s: Dreams of Greatness

By the summer of 1920, and the first anniversary of the founding of the International Optimist Club, the original 11 Optimist Clubs had grown to 17, with more than 3,000 men listed as members. At the second convention, held in St. Louis, delegates re-elected William Henry Harrison to the presidency, the only person in the organization’s history to serve two terms as president. Harrison was the assistant superintendent of agencies for a large life insurance company and as part of his duties he traveled throughout the U.S. as an agency inspector.

These trips on company business frequently took him to the widely scattered cities where Optimist Clubs existed. This allowed him to visit the clubs without cost to him or the fledgling organization, which in those early years struggled to find money in its treasury for postage stamps much less travel for its president. At the third convention in Springfield, Illinois, a real estate developer from St. Louis, Cyrus Crane Willmore, was elected president.

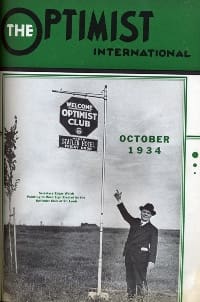

During the 1921-22 year, Willmore traveled all over the United States at his own expense, strengthening and inspiring existing clubs and creating new clubs at the then-phenomenal rate of almost two a month. At the end of his term as president of the International Optimist Club, Willmore delivered a convention address in which he laid out his dream of a great service organization “based on positive living and an affirmative philosophy.” Willmore used that optimistic philosophy in his professional life after serving as president as he became a millionaire within the next few years only to see it wiped away in the Great Depression. Calling on his “affirmative philosophy,” he later made another million before he died. The Optimist Magazine From its inception, the lines of communication between clubs and individual members were strengthened by The Optimist magazine. The first edition was published in October 1920.

Each of the 27 clubs in existence was requested to appoint a “scribe” to report in at least once a month with news of his club, suggestions for the entire organization and optimistic thoughts about things in general. On the front cover of some of those early issues appears a moon-shaped, smiling face. This beaming countenance had been suggested by a St. Louis Optimist as the official emblem of the International Optimist Club and it was so voted by the executive committee in August 1922. Along with the smiling face there appeared another symbol with the sun in its center and the words “Friendship, Sociability, Loyalty, Reciprocity” around it as a border. The Optimist magazine is today one of the longest continually published magazines in North America, with issues published and sent to every Optimist Club member from that 1920 first edition to the present.

The 1930s:

Optimism and the Great Depression By the time of its 10th anniversary, Optimist International was beginning to experience the growing pains of an organization expanding over the land faster than its succeeding administrations could keep up with it. From a few enthusiastic Clubs functioning in a few far-flung cities, the organization had grown to 117 Clubs in its first decade, with more than 8,000 members in the United States and Canada.

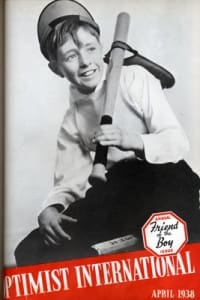

And while Optimism was high at that summer of 1929 meeting, dark clouds were looming in the world that would put heavy pressure on the fledgling organization’s efforts to survive. On October 29, 1929, the U.S. stock market crashed. The Great Depression was on. Hardly on its feet, Optimism now faced its greatest challenge. Never were its philosophies so sorely needed; never before had the opportunity to serve been so great. With each passing month the need for someone, some organization, to indeed be a “Friend of the Boy” became more and more acute. Many Optimists themselves were caught up in the swirling tide and, unable to maintain their own incomes, were forced to withdraw from their Optimist Clubs. Membership rosters across the land began to dwindle. The International program suffered in turn as revenues from dues diminished. More money was needed in the International treasury to meet its obligations and to take up the slack caused by certain Clubs that were having a tough time, too, and were falling behind their dues.

Things didn’t improve over the next few years. In fact, at a meeting of the Executive Committee of Optimist International, 1933-34 International President V. Ernest Field reported an emergency within the organization, a crisis comparable to that of the United States government itself. “Losses in numbers and in morale, due to the time,” he said, “are so heavy that if continued can mean the end of Optimist International.” To counteract this, he proposed a plan of progress built on fellowship, reciprocity, membership, boys work and new Clubs. “Our objective,” Field declared, “must be a net gain of 1,500 members in Clubs and 150 new Clubs!” The old concept of reciprocity—“I’ll scratch your back if you scratch mine”—had served the organization well in its early years but had gradually been replaced with a sense of mission to perform boys work. However, on hearing Field’s plan, most Optimists declared that they would be willing to go back to the old precept of reciprocity if it would gain new members and retain the old ones.

They did so with some misgivings, however, for the old timers among them cautioned of a lesson once learned, that men who became Optimists primarily to get business from their fellow Club members, and who subsequently failed to get the business they had anticipated, soon resigned, let their membership lapse or at least became inactive. During the years of the Great Depression, Optimist International’s role as “Friend of the Boy” was needed more than ever before. In the early 1930s, Clubs were encouraged to cooperate in a publicity program by placing signs along roads that led to their cities.

Therefore, at the 1935 convention in St. Louis, Optimists agreed as a matter of policy that business reciprocity among members was normally the natural result from close contact and friendship among those who worked together for others, and that too much emphasis on it for purposes of gaining members or in new Club building could be harmful. Concern was also noted that an ambitious boys work program might throw too great a responsibility on already financially embarrassed Club members and that elaborate and expensive programs for boys were creating a burden beyond what could be called reasonable during a financial crisis. And while 16 new Clubs had been established during the 1933-34 year—built by professional organizers – the funds of Optimist International were running low. Several members, most of whom had been active from the start of the organization, signed a note together for sufficient funds to operate for the balance of the year. Shortly before the 18th annual convention in Fort Worth in 1936, Immediate Past International President Henry Schaffert approached International President Walter J. Pray with a plan to help raise funds to keep the organization going. He admitted that the plan wasn’t original with him because he had seen it work with other organizations and several country clubs. Pray agreed with the proposal and allowed Schaffert to address the delegates.

The 1940s

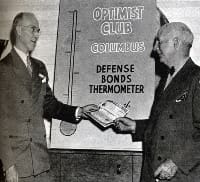

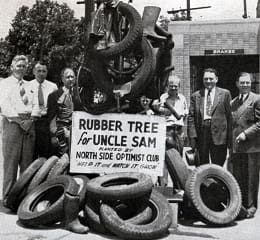

Clubs collect towers of rubber tires during the war. Junior Optimist boys help with the cause. On September 1, 1939, Nazi Germany marched into Poland. Two days later Great Britain and France declared war on Germany. A week later, on September 10, Canada entered into the war. The surprise attack by Japan on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, forced the United States into the global war. In both Canada and the United States all efforts turned to the all-out war pursuit.

Civilians turned full attention and devoted every effort to production of materials for war. There was some sentiment at the time that all service clubs should be disbanded for the duration of the war. Of course, Optimist Clubs in both the U.S. and Canada had been quick to pledge their support to their governments and to promise manpower necessary for all community wartime projects. One of the most necessary of those projects was the collection of scrap metal to make up for the normal peacetime supplies that would soon be exhausted in the all-out manufacture of arms and munitions. The U.S. called upon its citizens to salvage 17 million tons of scrap metal.

Optimist International immediately sent instructions to all Clubs on how to organize, publicize and conduct such a campaign in their respective communities. Following the first such campaign, it was learned that an average of 25 Optimists per Club had worked to collect scrap metal, and that more than 250 Clubs had produced an average of 12 1/2 tons of vital material. Optimist International received a special citation from the War Production Board for its achievements in collecting thousands of tons of sorely needed scrap metal and rubber. Optimists’ concerted effort in this and many subsequent home front campaigns during World War II is considered by many as the organization’s highest achievement.

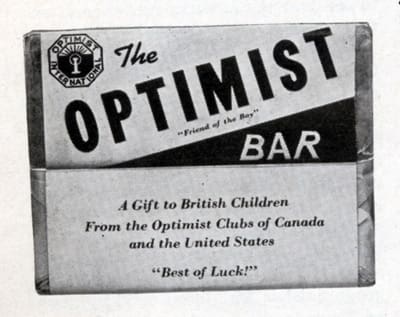

In Canada there was growing concern over the needs of children living overseas where the fighting was. Out of this concern arose a project that spread across the nation, appealing to hundreds of thousands of Canadians. Originating with the Optimist Club of Welland, Ontario, it was based on the conviction that children were entitled to a few little luxuries just because they are children and that the war had deprived them of these as well as many of life’s necessities. British children show off their chocolate, courtesy of Optimists overseas. The Chocolate Fund sent more than 2 million bars of chocolate to children. With the Optimists leading the way, the Chocolate Fund was established to pack and deliver to British children, through the British Food Ministry, the schools and the Red Cross, more than two million bars of chocolate. For thousands of youngsters this was the only sweet they knew during ten years of war. The value of Optimist International to the war effort was proved in many other ways time and again. Millions of dollars were raised in Optimist-sponsored bond drives. More than 1,600 Life Memberships were purchased with $100 war bonds. Servicemen’s centers at home were provided and staffed by Optimists.

Untold thousands of servicemen overseas received letters and gifts from the Optimist Clubs in their hometowns. By the end of the war nearly 2,000 Optimists were in uniforms of the Canadian and United States militaries. Nearly 1 out of every 7 members served their country during this time. Along with every other organization, Optimist International found its efforts to grow severely restricted by the war. Its field staff resigned in 1942 to enter military service and new Club building came to an abrupt standstill. Fewer than a dozen new Clubs were chartered during the war years. Surprisingly, however, total membership actually increased during this period, from 13,000 in 1941 to 16,000 in 1945. The wartime service efforts of Optimist Clubs attracted many who could not serve their countries in the military but felt they were contributing by getting involved in an organized effort on the home front. During the years of World War II there were no international conventions because of travel restrictions and the need for every Optimist to remain on the job until the war was won. Conferences were held instead to carry on the administrative work of the organization. The training of incoming Club and District officers became, for the first time, the responsibility of the District Governors. More than 1,600 Optimists purchased Life Memberships with $100 bonds.

At the 1942 Wartime Conference reports were received that despite the huge efforts of Clubs to contribute to the war effort boys work had not suffered. In fact, the average amount of time and money per Club devoted to youth service had increased throughout the organization. Although the curtailment of normal activities had resulted in Optimist International being in the best financial condition in its history, it faced the baffling problem of membership turnover. The average Club was experiencing a turnover of around 25 percent, nearly twice that of normal times, due in part to the unsettled conditions of nations at war. To meet this problem, Optimist International established a goal of 500 Life Memberships to provide for the postwar building of new Clubs.

By 1944, nearly 600 had been sold and the organization was ensured a sound financial structure upon which to build when the war came to an end.

The 1950s

As Optimists returned from serving their country in World War II and exchanged uniforms for civilian clothes, Clubs turned from wartime projects to their own campaigns of enlarging and strengthening their organization by recruiting new members. From 1950 to 1960, Optimism spread at a rate never before seen in its history.

While 700 Clubs and just over 38,000 members started the decade, the ten-year period ended with 1,871 Clubs consisting of over 73,000 members. Two significant creations occurred during the 1950s: club sponsorship of new Clubs and the awards program. The club sponsorship program in 1950, in which Optimists went out and built new Clubs themselves rather than leaving this work in the hands of paid organizers, transformed the organization. The building of nearly 1,200 Clubs during the first decade of this program nearly doubled what the paid field staff had been able to do in the first 30 years. The creation of what was originally known as the “Achievement and Awards Program” during the 1950-51 year helped recognize those individuals, Clubs, Zones and Districts for their efforts in growing the organization.

While there was nothing revolutionary in the recognition of effort, the program did provide a new level of excellence toward which Optimists could work and a system by which they could measure their accomplishments. As the 1950s begin, so does the awards program. Youth Appreciation Week The creation of Youth Appreciation Week is reason to celebrate for Optimists and youth everywhere. On a bitter cold winter night in 1955 near the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina, Optimist T. Earl Yarborough and his wife were driving back home to Charlotte after assisting in the organization of a Junior Optimist Club in Morganton. Under normal conditions the drive would have required less than two hours. That night, however, an icy glaze stretched their trip to five hours and the Yarboroughs had ample time to talk and to reflect on the incidents of the evening. “It beats me,” said Earl. “On a night like this every one of those kids showed up for the meeting. Some of them had to walk several miles, I understand. They must be pretty good kids to be so enthusiastic over their new Junior Optimist Club.” Then, almost as an afterthought, he added, “I wonder what the morning papers will have to say about this. Nothing, in all probability, for it’s really not great news. If those boys had been arrested for swiping hubcaps or cutting tires or something though, there would have been a story about that.” It was a shame, the Yarboroughs agreed, that so much public attention is paid to teenagers who go wrong and so little to those who stay right. By the time he reached his home, Yarborough had the conviction that Optimists should and could do something about it. He armed himself with statistics on juvenile delinquency and on juvenile decency. He solicited the aid of two fellow Optimists, Harold Smoak and a Charlotte newspaperman, Kays Gary.

He carried his idea for a Youth Appreciation Day to his own Optimist Club and to the North Carolina statehouse, where the governor of the state gave his enthusiastic endorsement. On May 22, 1955, North Carolina observed the first Youth Appreciation Day. The following year Optimist International scheduled a Youth Appreciation Week program on a pilot basis in five states and one Canadian province. Acceptance of the program and eager participation in it were reported from every trial area. In the autumn of 1957, Optimist International launched its first organization-wide program that had as its sole purpose the “recognition, commendation and encouragement of the 95 percent of all teenagers whose feet are firmly planted on the right track and from whose midst will come the adult leaders of tomorrow’s world.” More than a thousand Optimist Clubs held Youth Appreciation Week programs that first year.

The number increased steadily and the program continues to be the most popular of all of Optimist International’s programs. With his signature, U.S. President Richard M. Nixon makes official the first Youth Appreciation Week. Youth Appreciation Week hit its high water mark in 1971 when the United States Congress by joint resolution passed Public Law 92-43. It designated the week beginning the following November 8 as Youth Appreciation Week. On November 5, 1971, in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, D.C., U.S. President Richard M. Nixon signed the first Youth Appreciation Week proclamation in the presence of Immediate Past International President Charles C. Campbell, Optimist T. Earl Yarborough, sponsors of the bill in both Houses of Congress and 21 young people from 12 states.

The 1960s

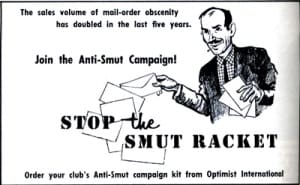

As Optimists continued waging a campaign against the illegal use of drugs, they resolved to wage a similar battle against pornography. At the 1960 International Convention, delegates passed a resolution urging all Optimist Clubs to conduct local campaigns to stop the increasing traffic in mail order pornography.

To help Clubs wage these campaigns, Optimist International prepared a comprehensive anti-smut kit, providing step-by-step information on how a Club could alert its community to “the evil that was being spread by mail throughout the land.” At about the same time, Optimist International began publishing a booklet called “A Boy Today, A Man Tomorrow.” Written by medical professionals, the booklet explained in simple terms what was called “the many mysteries of growing into manhood.” Clubs were encouraged to give it to health educators, doctors, nurses, teachers and parents in their communities.

Within the first two years of its existence, more than 50,000 copies had been distributed, and by the 1990s it was estimated that several million copies of the little booklet had been put into circulation. With the ever-increasing fear of nuclear war, delegates at the 1961 convention passed a Home Shelter resolution urging Clubs and communities to safeguard their homes and families against the threat of radioactive fallout with adequate home shelters.

The resolution also asked Clubs to conduct programs of public information and education in their communities to point out the need for home fallout shelters. Highlighting that 1961 gathering of Optimists was an address by former U.S. Vice President Richard M. Nixon, who had lost the most recent presidential election to John F. Kennedy. Speaking to the 2,500 Optimists and their family members, Nixon said, “I have spoken to many individual service club meetings, but Optimist has a certain lift to it. The name itself simply warms you up and brightens you as you get an invitation or as you see the Optimist banner on the wall of a service club meeting place.” Optimists began the 1960s with an anti-smut campaign (above). Not long after, a booklet titled A Boy Today, A Man Tomorrow was first published. It is estimated that several million copies of the booklet were produced.

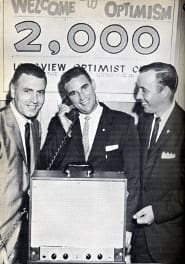

Addressing the 1961 Optimist Convention, Richard Nixon said, “I have spoken to many individual service club meetings, but Optimist has a certain lift to it.” A long-distance “conference call” from Omaha, Nebraska, became a highlight in the organization of an Optimist Club in Longview, North Carolina, in October of 1961. The Optimist Club of Longview, Hickory, North Carolina, became the 2,000th Club to join Optimist International and the long-distance call came from International President Raymond R. Rembolt, who was in Omaha visiting another Optimist Club there. The event celebrated the addition of more than a thousand new Clubs during the previous seven years. The 2,000th Club, the Optimist Club of Longview, North Carolina, receives a congratulatory phone call from International President Raymond R. Rembolt.

The 1970s

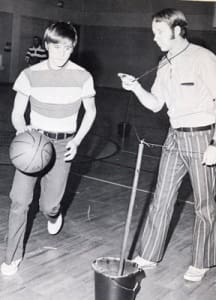

As the 1970s began, the organization continued to develop new programs for the development of young people. The Tri-Star Basketball program for boys 9 to 12 years of age was adopted. The first year of the program saw more than 300 Clubs and 75,000 youngsters participate.

Competing with others their own age, boys demonstrated their skills at passing, shooting and dribbling. As it grew in popularity, the Tri-Star program was later expanded to include football, baseball, golf and hockey, and began to offer opportunities for girls to participate also.

In 1972, the Opportunity for Involvement Club program was adopted. An Opportunity for Involvement Club was made up of young men and women in the 10th, 11th and 12th grades and the upper four grades in Canada. The Club served as a vehicle through which they could become active and involved in solving problems that challenged their community and society. As the ecology movement grew in society, Optimists became involved through the L-I-F-E (Living is for Everything) program. It was a program through which a Club could educate, stimulate and lead its home community in an organized battle for clean air, pure water, uncluttered streets, proper disposal of trash and junk, and a quiet atmosphere. On October 15, 1972, 70 of North America’s top community leaders, hand-picked for their prestige, expertise at getting things done and their awareness of a mounting social problem, venereal disease, gathered in St. Louis at the request of Optimist International.

They had come for the two-day seminar, financed by a grant of $20,000 by the United States government, to consider the problem and what could be done about it. Tri-Star is born with a basketball program. In this photo, 13-year-old Kevin Beecher shows off his dribbling technique as John Price of the Optimist Club of Coatesville, Pennsylvania, times him. Optimist International, with the launching of its program AVOID in 1972, became one of the first service club organizations to move in a direction to conduct an active program to combat syphilis and gonorrhea. As the programs of the organization became more inclusive of all children, boys and girls alike, the organization once again altered its motto from “Friend of the Boy” to “Friend of Youth.” In 1974, after several discussions with officials of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Optimist International launched another new program called “Adopt a Neighborhood.” The program recommended that a metropolitan Club select a definable small area in an inner-city neighborhood, such as a public housing development. A youth center, church or school would be used as a focal point. While the main objective of the Optimist volunteers was to provide service, guidance and help to disadvantaged youth, they were also to serve the entire community. As the decade of the 1970s entered its final years, Optimists looked for more new programs and challenges to which they could turn their efforts.

In 1978, the organization developed the Optimist Junior World Golf Tournament. 1978-79 International President Dudley Williams of San Diego had initiated discussions of co-sponsoring one of the most prestigious junior golf events in the world with the San Diego Junior Golf Association. Optimist Clubs and Districts began holding qualifying tournaments to advance their best young golfers to the annual championships held at the Torrey Pines courses in San Diego. The tournament featured over 700 young golfers annually competing in five age groups.

In 1975, the organization decided the time had come to be able to offer more young golfers from its District qualifiers the opportunity to participate at an international level. That summer, the Optimist International Junior Golf Championships were born at Doral Country Club in Miami, Florida. The following year the championships were relocated to the PGA National golf courses in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, where the prestige of “The Optimist,” as it has come to be known among the young golfers, continues to grow. And while many Clubs were helping the gifted young athletes in their communities, others jumped on the bandwagon when the Help Them Hear program was rolled out for introduction in the 1978-79 year. Help Them Hear offered many Clubs a chance to do something for those young people, and adults, who were hearing impaired. The program was designed so that Clubs could implement programs to heighten public awareness of the problems associated with hearing impairment; and to provide local testing facilities as well as corrective and educational techniques for those with hearing problems.

The program led to the formation of the Communication Contest for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (CCDHH), which shared equal billing with the Oratorical and Essay contests. Optimist International President Dudley D. Williams presents a trophy to Monty Leong, winner of the boys 15-17 division in the first Optimist Junior World Championships. At a 1973 Michigan-Illinois football game in Ann Arbor, Michigan, the band pays tribute to Optimists and youth prior to the game, as 80,000 spectators enjoy the celebration. Optimist International celebrates 3,000 Clubs as the Optimist Club of Dumbarton, Maryland, is chartered in 1972.

The 1980s

The cover of The Optimist, June 1984 800 youth boldly “Just Say No” in an Optimist TV commercial. A special Optimist program for high school students, the Essay Contest, was launched in 1983. Students are asked to write an essay on an assigned topic as they compete for top honors at the Club level. Winners are then entered in District competition and from the District winners, an International-level winner is selected.

The contest continues to be one of the most popular service projects conducted by Optimist Clubs today. In 1985, Optimist International endorsed the national Just Say No program and introduced an anti-drug program for use by Clubs. Optimists recognized that drug abuse was the most serious problem facing young people at the time. Because peer pressure was considered the major reason why young people experiment with drugs, the major thrust of Just Say No was to counter this peer pressure.

Although Optimists were just one of many supporters of Just Say No, they were perhaps the most active. Less than two years after launching its program, Optimist International had already reached nearly 1.5 million children in nearly 10,000 schools. Optimist Youth Clubs took a major step forward the weekend of September 9-11, 1988. Delegates representing Youth Clubs from throughout the organization held their first international convention and formed an international organization, Junior Optimist Octagon International, to become known more familiarly as JOOI. Elected as their first international president was Adriana Johnson of San Antonio, Texas. The 1980s was a decade of tremendous growth.

In the first 50 years of the organization’s existence, Optimist Club membership grew steadily until hitting the 100,000 mark in 1969. However, just over a decade later, membership topped the 130,000 plateau in 1980. And by the end of the decade, Optimist International reached the zenith of its membership rise with over 175,000 members. The continued growth of Optimist International was apparent not only in th e number of members and Clubs, but in the corresponding number of Districts. As Districts grew larger it became more difficult for the District leaders to give as much of their time as they would have liked to each Club. Deeming it necessary to sub-divide existing Districts, the International Board of Directors, between 1981 and 1986, expanded from 38 to 50 the number of Districts. The province of Ontario was divided into four Districts and the state of North Carolina into three. Missouri, Indiana and Florida were each divided into two Districts, and two new Districts were formed from the former Pacific Southwest District. The most significant geographic change from the 1960s through the 1980s was the growth in Quebec. In 1966, there were only 36 Optimist Clubs in that Canadian province. That number swelled to over 350 by 1980, when the organization had its first French-Canadian International President, Lionel Grenier of Terrebonne, Quebec.

The first youth convention took place in 1988 and was the beginning of Junior Optimist Octagon International. Growth in Quebec was staggering during this period. In 1977-78, 52 new Clubs were built. Two years later, 60 new Clubs were formed in Quebec, a record for any District that still stands. By October of 1988 when Fernand Rondeau of Montreal assumed the presidency, Optimist International had over 30,000 members in over 700 Clubs in Quebec, which at the time represented nearly 20% of the entire organization.

The 1990s

1997-98 International President J. Wayne Smith’s theme was “Renaissance, Commitment to Growth.” It epitomized the entire 1990s for the organization. Optimists spent the decade reigniting their spirit of Optimism, revitalizing Club programs, recruiting new members and serving more children. International President Kenneth E. Monschein jump-started the 1990s with a call to action in 1989-90.

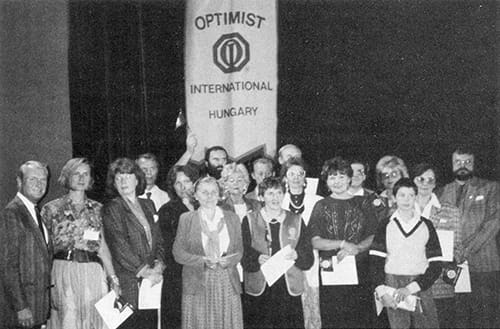

That year, Optimist International experienced its largest growth in history with 318 new Clubs chartering and more than 20 associate Clubs forming in Hungary. For the first time, Optimism had spread outside of North America. Clubs continued to spring up in areas previously untouched by Optimism. Realizing the untapped opportunities and the importance of expanding overseas, delegates to the 1992 International Convention in Anaheim, California, approved a one dollar dues increase for international expansion. These funds would be earmarked to build Clubs, add members in foreign countries and service these new Clubs and members. In a quick response, the Optimist Club of Berstett, France, incorporated on July 7, 1992; the Dubna Optimist Club of Russia formed in March 1993; and the Optimist Club of Hanover, Germany, joined soon after on August 16, 1993.

International President Ken Monschein presents charter certificates to Presidents of 17 Clubs at a District convention. Executive Director Richard E. Arnold congratulates Dr. Wulf Krause on Germany’s first Optimist Club. Next, Optimists moved to the Pacific Rim and initiated their first Club in the Philippines on September 1, 1995. Less than a year later, five more Clubs had been chartered in that country. Building on that success, Optimists headed to China, where on January 19, 1997, the First Kaohsiung City Optimist Club chartered in Taiwan with 50 members. These proud new Optimists were initiated before 160 government officials, guests and family members. Just a few days later the First Hong Kong Optimist Club formed with 30 charter members, and by May the First Kaohsiung City Club had already sponsored its first new Club, the First Taipei City Optimist Club.

On the home front growth ignited in the Northeastern U.S., and in October 1990 the New England District formed with 17 Clubs. After a 10-year absence, Optimism returned to Alaska when the Fairbanks Optimist Club formed in July 1992. But the most significant expression of Optimism occurred on the island of Jamaica. While a Club had existed in Kingston since 1980, the late 1980s and early ’90s saw an explosion of growth in that country. So much so, in fact, that in the 1992-93 year, the Jamaica District was formed under the leadership of its first Governor, Theo Golding of Kingston, who would go on to become the first International President from a country other than the U.S. or Canada in 2007-08. Optimist Clubs began springing up all over the tiny island and soon overflowed to neighboring islands such as Barbados, the Cayman Islands, Trinidad and many others. In 1997-98, the District changed its name to the Caribbean District to more accurately reflect its outreach. The renaissance spirit flowed into every facet of the organization, and international programs were no exception.

With their revitalized attitude, Optimists began researching new programs and revamping old ones. Optimists were dedicated to educating youth about the very real dangers of steroids. In the early 1990s, substance abuse prevention continued to top the list of concerns in North America’s schools and communities. Wanting to help where kids needed them most, Optimists immediately reacted by supporting drug prevention and education programs. Soon, the International Office functioned as a clearinghouse for individual Clubs by providing resources to individual members. In addition to embracing Just Say No, Optimists now dedicated themselves to additional drug-deterrence programs such as Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE); Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD); and Students Against Steroids (SAS). Optimist International also adopted the “Get Real” program, which educated students on the life-threatening problems caused by steroid use. Help Them Hear, another well-received Optimist program, pointed members toward a new endeavor. In 1990-91, Optimists took their involvement with the hearing impaired one step further by developing the Communications Contest for the Hearing Impaired (which later became the Communication Contest for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, CCDHH). The CCDHH program, run much like the Oratorical Contest, had youths making a presentation in voice or sign language on a pre-assigned subject before a panel of judges. CCDHH started as a pilot with 13 Districts, but thanks to its tremendous success scholarships were made available to all Districts. In 1992 the Optimists in Action Day pilot program set out to unite hundreds of volunteers in a single day of community service. Optimists in seven randomly selected Districts made such a positive impact on their communities that the Board of Directors approved Optimists in Action Day as an annual international program. To keep up with the pace of children, the age-old Bicycle Safety Week expanded to Safety on Wheels in 1995. This broadened program covered all “wheeled” activities such as in-line skating, skateboarding, car and bus riding and driving. Optimists responded promptly to parents’ fear of rising violence as they did to drug concerns. On May 6, 1995, the first Optimist Day of Non-Violence was incorporated into the existing Respect for Law program. Optimists created this day as a way for their Clubs and communities to jointly prevent violence and promote peace and harmony.

Optimists provided these deserving youth an opportunity to complete for scholarships. Over the years, Optimists have focused on mentoring to remain a positive influence in children’s lives. This dedication became a marketing focus to attract corporate involvement, and in 1996 Morton International sponsored Optimist International’s newest program, “Always Buckle Children in the Back Seat” (ABC) public awareness and education campaign. Clubs distributed brochures and support material to educate caregivers on the dangers of kids sitting in the front seat of a vehicle with passenger side airbags. At the end of the program’s inaugural year, requests for more than 3.5 million brochures deluged the International Office.

A New Millennium: 2000

As people worldwide celebrated the dawn of the new millennium, Optimist International celebrated greater achievements in its service to youth. While respecting the organization’s traditions of the 20th century, Optimists forged into the new millennium with renewed enthusiasm and a fresh perspective on how best to serve youth in the 21st century. One of the first things the Board of Directors did was place more importance on marketing the services and programs the organization offered. Adopting the slogan “Optimists … Bringing Out the Best in Kids,” the organization put specific emphasis on the mission of Optimist Clubs without de-emphasizing the standard bearer “Friend of Youth.”

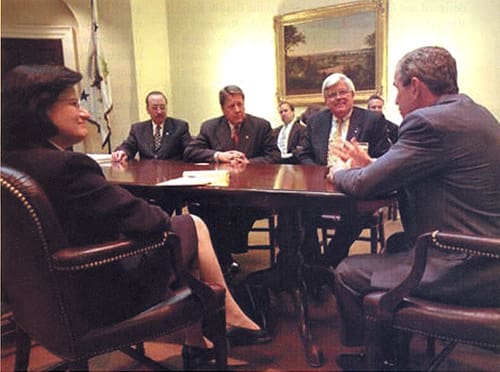

On July 2, 2001, then International President Bob Garner was invited to the White House along with the leaders of other service club organizations to meet with U.S. President George W. Bush. The meeting of the “volunteering minds” was called so Bush could unveil his plan to recruit one million mentors for the nation’s youth. Garner and his fellow community service leaders met briefly with the President and First Lady for an open press conference before heading into the Oval Office for more discussions. The next day, Garner addressed the delegates at the International Convention in Orlando about his visit. “Of great importance,” he told the gathering of Optimists, “is the fact that at no time in recent history, or possibly ever, had the presidents of the world’s four largest service organizations assembled with the president of the United States to commit their collective strength and energy behind a common effort. And, of great importance to Optimist International, is that it is an effort clearly designed and focused on ‘Bringing Out the Best in Kids.’ Bob Garner, 2000-2001 International President shares a few kind words with US President, George W. Bush. “President Bush asked the respective presidents if we could, collectively, directly touch the lives of one million kids in the next four years. We each pledged that this was not only possible, but also a clearly attainable goal.” Just a few months later, the Board of Directors endorsed the Optimist Childhood Cancer Campaign as the organization’s focal point for serving youth in the years ahead.

The Optimist Childhood Cancer Campaign (CCC) was designed to support young people with cancer, to support cancer patients’ families and caregivers, provide support to healthcare providers, and to help childhood cancer research. Optimists saw childhood cancer as the ultimate test, with the organization having both the manpower and the willpower to defeat this devastating disease. No other service organization had put its international resources on the line to rid the world of childhood cancer. In just the first few months after kicking off the program, Optimist Clubs began responding. In the Midwestern and Southwestern Ontario districts Optimists committed to raising one million dollars for the new Children’s Hospital of Western Ontario. Optimists in the Pacific Northwest District volunteered more than 1,500 hours to serve more than 3,700 kids with cancer and their family members. And in South Carolina, the Greater Spartanburg Optimist Club teamed up with the Cherokee County Cancer Society to provide transportation and lodging for families who have children requiring oncology treatment who need to travel to pediatric care facilities in North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia.

To better meet the goal of defeating childhood cancer, the organization committed to raise nearly one million dollars to fund a research fellow at Johns Hopkins University in Maryland, who would be devoted to finding a cure for childhood cancers. By the end of the decade, Optimists had reached the monetary goal. While donations continued to fund the fellowship, other donations to the CCC program allowed the organization to start a Club matching grants program for Clubs to run their own programs under the childhood cancer umbrella. This childhood cancer patient was given a laptop by an Optimist Club to assist her in keeping in touch with her friends during treatments.